A Childhood of Curiosity and Loss

Clive Staples Lewis, known to the world simply as C.S. Lewis, was born in Belfast, Ireland, in 1898. From a young age, his mind brimmed with imagination. He loved fairy tales, Norse myths, and stories of talking animals. But his childhood was also marked by deep grief—at the age of ten, he lost his mother to cancer. That wound, coupled with the harshness of early boarding school experiences, shook his faith and planted the seeds of skepticism.

Lewis was intellectually gifted and always searching for meaning. He devoured books, explored different philosophies, and developed a love for writing. By his teenage years, he declared himself an atheist, convinced that Christianity was little more than a myth.

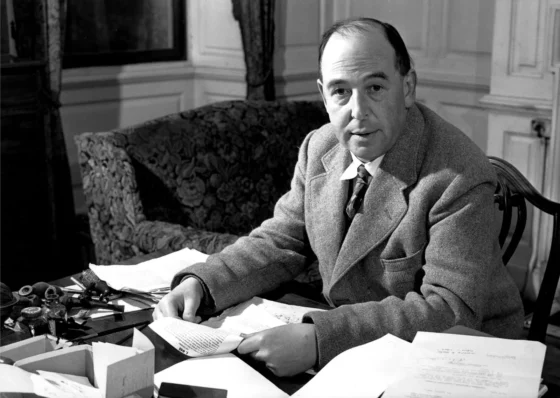

The Academic Mind

Lewis’s brilliance carried him to Oxford University, where he studied classics, philosophy, and English literature. His education was interrupted by World War I. He fought in the trenches of France and was wounded in battle. That brutal reality of war left scars, both physical and spiritual, but also gave him a perspective on suffering that would later shape his Christian writings.

After the war, Lewis returned to Oxford and distinguished himself as a scholar. He became a tutor and later a fellow of Magdalen College, specializing in English literature. His lectures were said to be captivating—he could bring life to medieval texts, Chaucer, and Milton in a way that made students lean forward with interest.

But at this stage, Lewis was still a skeptic, clinging to his atheism. He once remarked that he was “the most reluctant convert in all England,” but the journey to that conversion was already underway.

The Influence of Friendship

One of the most pivotal factors in Lewis’s transformation was friendship. At Oxford, he found himself surrounded by men who were not only brilliant but also deeply committed Christians. J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings, became one of his closest friends. Another was Hugo Dyson, a fellow scholar.

These friendships challenged his assumptions. Late-night conversations often circled around faith, myth, and truth. Lewis loved mythology but dismissed Christianity as false. Tolkien, however, argued that the story of Christ was not just another myth but the “true myth”—the myth that became fact.

This struck Lewis profoundly. The idea that God could enter history, that myth and reality could converge, began to soften his resistance. Slowly, his intellectual walls crumbled.

The Reluctant Conversion

Lewis’s conversion was not sudden but gradual, stretching across years of thought and wrestling. He first admitted to the existence of God, abandoning atheism. But he was not yet ready to embrace Christianity fully. That moment came in 1931, during a late-night walk with Tolkien and Dyson along Addison’s Walk in Oxford.

They spoke of Christ’s sacrifice, of the incarnation, and of redemption. A few days later, Lewis described his realization with simple honesty: “When we set out, I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did.”

For a man who had resisted faith so strongly, this was no small shift. He surrendered, not out of blind acceptance, but through deep intellectual conviction.

The Christian Writer Emerges

Once Lewis embraced Christianity, he poured his energy into writing about it. His pen became one of the most powerful tools of Christian apologetics in the 20th century. He wanted to explain faith in a way that ordinary people could grasp.

His book Mere Christianity, adapted from radio talks he gave during World War II, became a cornerstone of modern Christian thought. It stripped faith down to its essence and presented it with clarity and reason. His ability to bridge intellectual rigor with simple explanation made the book timeless.

Another masterpiece, The Screwtape Letters, took the form of fictional correspondence between a senior demon and a junior tempter. Through satire and sharp wit, Lewis exposed the subtleties of temptation and the realities of spiritual warfare.

And of course, his most beloved works—the Chronicles of Narnia—captured the imagination of children and adults alike. In those seven books, he combined fairy tale wonder with Christian allegory. The character of Aslan, the great lion, became for many readers a glimpse of Christ’s sacrificial love.

Accolades and Influence

Lewis’s career was not confined to Christian writing. He remained a respected academic, producing scholarly works on medieval and Renaissance literature. He taught at Oxford for nearly three decades before becoming Chair of Medieval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge University.

But it was his Christian writings that earned him a global following. He became one of the best-selling authors of all time, with more than 200 million copies of his books sold worldwide. The Chronicles of Narnia alone has been translated into dozens of languages and adapted into stage plays, radio dramas, television series, and blockbuster films.

In 1956, Lewis married Joy Davidman, an American writer. Their love story was brief but profound. Joy’s battle with cancer tested his faith again, but also deepened his understanding of love, loss, and God’s purposes. He chronicled his grief after her death in A Grief Observed, one of the rawest and most honest works on suffering ever written.

A Legacy of Faith and Imagination

C.S. Lewis passed away in 1963, on the same day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. His death went largely unnoticed in the headlines, but his legacy only grew stronger with time.

What makes Lewis’s story so compelling is not just his achievements but the transformation he underwent. He began as a wounded boy who turned away from God, became a hardened atheist, and rose to prominence as an academic skeptic. Yet, through friendship, intellectual honesty, and personal searching, he became one of Christianity’s greatest defenders.

Lewis’s writings continue to resonate because they are deeply personal yet universally relevant. He did not write as a man who had all the answers but as one who had wrestled with doubt and come through it with faith intact. He showed that Christianity is not just for the simple-minded, nor is it opposed to reason. Instead, it is the ultimate fulfillment of both heart and intellect.

Conclusion: The Scholar Who Believed

C.S. Lewis’s life is a testament to the power of transformation. He was a man who resisted faith yet could not escape its call. He was an academic who could have remained in the ivory towers of scholarship, but he chose instead to speak to ordinary people. He was a writer who used his imagination not only to entertain but also to reveal eternal truths.

His journey from atheist to Christian, from skeptic to believer, remains one of the most compelling faith stories of the modern age. And his works continue to invite readers into a world where reason and wonder, scholarship and faith, come together.

For millions, C.S. Lewis is not just an author to admire but a companion in the search for truth. His legacy is not merely in the books he sold or the accolades he earned, but in the lives he touched—and still touches today.